THE MAN FROM TISHIMINGO

Tomorrow (the last day of January) is the 75th birthday of Rick Hall, born in Tishimingo, Mississippi - the man behind Fame Studios and thereby the person who gave the late great Arthur Alexander his chance to record (for which he was amply repaid: see below). So happy birthday to Mr. Hall, and let me offer a brief account of his part in the Arthur Alexander story by reprinting the AA entry from The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia:

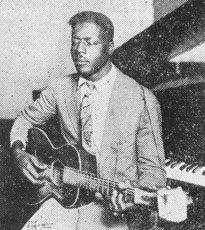

Alexander, Arthur [1940 - 1993]

Arthur Alexander was born on May 10, 1940 in Florence, Alabama, just five miles from Sheffield and Muscle Shoals. His father played gospel slide guitar (using the neck of a whiskey bottle); his mother and sister sang in a local church choir.

Dylan covers Arthur Alexander’s début single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’, made in 1959 and released under his nickname June Alexander (short for Junior), on his Down In The Groove album. You can’t say he pays tribute to Alexander with this, because he makes such a poor job of reviving it...

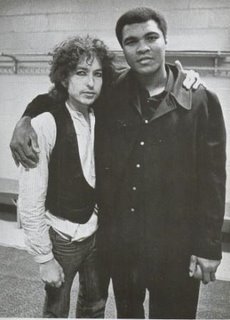

It was really with ‘You Better Move On’ that Arthur Alexander made himself an indispensable artist. He wrote this exquisite classic while working as a bell-hop in the Muscle Shoals Hotel. And then he made a perfect record out of it, produced by Rick Hall at his original Fame studio (an acronym for Florence, Alabama Music Enterprises), which was an old tobacco barn out on Wilson Dam Highway. Leased to Dot Records in 1961, ‘You Better Move On’ was a hit and helped Hall to build his bigger Fame Studio, which later attracted the likes of Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. In 1969 Fame’s studio musicians opened their own independent studio, Muscle Shoals Sound, where Dylan would later make his gospel albums Slow Train Coming and Saved.

Despite this hit and its influence on other artists, however, while an EP of his work was highly sought-after in the UK, Arthur Alexander was generally received with indifference by the US public and his career stagnated. After years of personal struggle with drugs and health problems (he was hospitalized several times in the mid-1960s, sometimes at his own request, in a mental health facility in southern Alabama), he returned in the 1970s, first with an album on Warner Brothers and then with a minor hit single in 1975, ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’.

One of Arthur Alexander’s innovations as a songwriter was the simple use of the word ‘girl’ for the addressee in his songs. When he first used it, it had a function: it was a statement of directness, it instantly implied a relationship; but soon, passed down through Lennon and McCartney to every 1964 beat-group in existence, it became a meaningless suffix, a rhyme to be paired off with ‘world’ as automatically as ‘baby’ with ‘maybe’. This couldn’t impair the precision with which Arthur Alexander wrote, the moral scrupulousness, the distinctive, careful way that he delineated the dilemmas in eternal-triangle songs with such finesse and economy. All this sung in his unique, restrained, deeply affecting voice. Rarely has moral probity sounded so appealing, so human, as in his work. Listen not only to ‘You Better Move On’ but to the equally impeccable ‘Anna’ and ‘Go Home Girl’ and the funkier but still characteristic ‘The Other Woman’.

Arthur Alexander is also one of the many R&B artists whose work was happy to incorporate children’s song, as so much of Dylan’s work does (most especially, of course, the album Under The Red Sky in 1990). Alexander’s 1966 single ‘For You’ incorporates the title line and the next from the children’s rhyming prayer ‘Now I lay me down to sleep’ (the next line is ‘And pray the Lord my soul to keep’), which first appeared in print in Thomas Fleet’s The New-England Primer in 1737.

The Rolling Stone covered ‘You Better Move On’; The Beatles covered ‘Anna’; and it was after Arthur Alexander cut Dennis Linde’s song ‘Burning Love’ in 1972 that Elvis Presley covered that one. Add to that the fact that Dylan covered ‘Sally Sue Brown’, and you have a pretty extraordinary level of coverage for an artist who remains so far from a household name.

After his 1975 hit, he went back on the road briefly but didn’t enjoy it; he felt he’d received no money from the record’s success and meanwhile he ‘had found religion and got myself completely straight’, so he quit the music business and moved north. By the 1980s he was driving a bus for a social services agency in Cleveland, Ohio, when, to his surprise, Ace Records issued its collection of his early classics, A Shot Of Rhythm and Soul - which included reissue of that first (and by now super-rare) single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’. His attempt at another comeback, in the early 1990s, yielded an appearance at the Bottom Line in New York City, another in Austin, Texas, and the Nonesuch album Lonely Just Like Me, which included several re-recordings. ‘Sally Sue Brown’ was one of them. As on the original ‘You Better Move On’, the musicians included Spooner Oldham.

It all came too late. Arthur Alexander died of a heart attack in Nashville on June 9, 1993. A few months earlier, on February 20, his biographer, Richard Younger, went to interview him, at a Cleveland Holiday Inn. ‘He told me,’ wrote Younger, that ‘he had no old photos of himself, nor any of his old records, and had never even heard many of the cover versions of his songs. I had anticipated this and brought along a copy of Bob Dylan’s version of “Sally Sue Brown”. With the headphones pressed to his ears, Arthur moved back and forth in his seat. “Bob’s really rocking,” he said.’ It was a generous verdict.

___________________________________________________

[Arthur Alexander: ‘Sally Sue Brown’, Sheffield AL, 1959, Judd 1020, US, 1960; ‘You Better Move On’ c/w ‘A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues’, Muscle Shoals AL, Oct 2 1961, Dot 16309, US, 1962; ‘Anna’, Nashville, Jul 1962, Dot 16387, 1962; ‘Go Home Girl’, Nashville, c.Sep 1962, Dot 16425, 1963; ‘(Baby) For You’ c/w ‘The Other Woman’, Nashville, 29 Oct 1965, Sound Stage 7 2556, US, 1965; ‘Burning Love’, Memphis, Aug 1971, on Arthur Alexander, Warner Bros. 2592, US, 1972; ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’, Muscle Shoals, Jul 1975, Buddah 492, US, 1975; A Shot of Rhythm and Soul, Ace CH66, London, 1982; Nashville, 12-17 Feb 1992, Lonely Just Like Me, Elektra Nonesuch 7559-61475-2, 1993. Special thanks for input & detail to Richard Younger, author of Get a Shot of Rhythm & Blues: The Arthur Alexander Story, Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2000; quote is p.168.]

Alexander, Arthur [1940 - 1993]

Arthur Alexander was born on May 10, 1940 in Florence, Alabama, just five miles from Sheffield and Muscle Shoals. His father played gospel slide guitar (using the neck of a whiskey bottle); his mother and sister sang in a local church choir.

Dylan covers Arthur Alexander’s début single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’, made in 1959 and released under his nickname June Alexander (short for Junior), on his Down In The Groove album. You can’t say he pays tribute to Alexander with this, because he makes such a poor job of reviving it...

It was really with ‘You Better Move On’ that Arthur Alexander made himself an indispensable artist. He wrote this exquisite classic while working as a bell-hop in the Muscle Shoals Hotel. And then he made a perfect record out of it, produced by Rick Hall at his original Fame studio (an acronym for Florence, Alabama Music Enterprises), which was an old tobacco barn out on Wilson Dam Highway. Leased to Dot Records in 1961, ‘You Better Move On’ was a hit and helped Hall to build his bigger Fame Studio, which later attracted the likes of Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett. In 1969 Fame’s studio musicians opened their own independent studio, Muscle Shoals Sound, where Dylan would later make his gospel albums Slow Train Coming and Saved.

Despite this hit and its influence on other artists, however, while an EP of his work was highly sought-after in the UK, Arthur Alexander was generally received with indifference by the US public and his career stagnated. After years of personal struggle with drugs and health problems (he was hospitalized several times in the mid-1960s, sometimes at his own request, in a mental health facility in southern Alabama), he returned in the 1970s, first with an album on Warner Brothers and then with a minor hit single in 1975, ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’.

One of Arthur Alexander’s innovations as a songwriter was the simple use of the word ‘girl’ for the addressee in his songs. When he first used it, it had a function: it was a statement of directness, it instantly implied a relationship; but soon, passed down through Lennon and McCartney to every 1964 beat-group in existence, it became a meaningless suffix, a rhyme to be paired off with ‘world’ as automatically as ‘baby’ with ‘maybe’. This couldn’t impair the precision with which Arthur Alexander wrote, the moral scrupulousness, the distinctive, careful way that he delineated the dilemmas in eternal-triangle songs with such finesse and economy. All this sung in his unique, restrained, deeply affecting voice. Rarely has moral probity sounded so appealing, so human, as in his work. Listen not only to ‘You Better Move On’ but to the equally impeccable ‘Anna’ and ‘Go Home Girl’ and the funkier but still characteristic ‘The Other Woman’.

Arthur Alexander is also one of the many R&B artists whose work was happy to incorporate children’s song, as so much of Dylan’s work does (most especially, of course, the album Under The Red Sky in 1990). Alexander’s 1966 single ‘For You’ incorporates the title line and the next from the children’s rhyming prayer ‘Now I lay me down to sleep’ (the next line is ‘And pray the Lord my soul to keep’), which first appeared in print in Thomas Fleet’s The New-England Primer in 1737.

The Rolling Stone covered ‘You Better Move On’; The Beatles covered ‘Anna’; and it was after Arthur Alexander cut Dennis Linde’s song ‘Burning Love’ in 1972 that Elvis Presley covered that one. Add to that the fact that Dylan covered ‘Sally Sue Brown’, and you have a pretty extraordinary level of coverage for an artist who remains so far from a household name.

After his 1975 hit, he went back on the road briefly but didn’t enjoy it; he felt he’d received no money from the record’s success and meanwhile he ‘had found religion and got myself completely straight’, so he quit the music business and moved north. By the 1980s he was driving a bus for a social services agency in Cleveland, Ohio, when, to his surprise, Ace Records issued its collection of his early classics, A Shot Of Rhythm and Soul - which included reissue of that first (and by now super-rare) single, ‘Sally Sue Brown’. His attempt at another comeback, in the early 1990s, yielded an appearance at the Bottom Line in New York City, another in Austin, Texas, and the Nonesuch album Lonely Just Like Me, which included several re-recordings. ‘Sally Sue Brown’ was one of them. As on the original ‘You Better Move On’, the musicians included Spooner Oldham.

It all came too late. Arthur Alexander died of a heart attack in Nashville on June 9, 1993. A few months earlier, on February 20, his biographer, Richard Younger, went to interview him, at a Cleveland Holiday Inn. ‘He told me,’ wrote Younger, that ‘he had no old photos of himself, nor any of his old records, and had never even heard many of the cover versions of his songs. I had anticipated this and brought along a copy of Bob Dylan’s version of “Sally Sue Brown”. With the headphones pressed to his ears, Arthur moved back and forth in his seat. “Bob’s really rocking,” he said.’ It was a generous verdict.

___________________________________________________

[Arthur Alexander: ‘Sally Sue Brown’, Sheffield AL, 1959, Judd 1020, US, 1960; ‘You Better Move On’ c/w ‘A Shot Of Rhythm And Blues’, Muscle Shoals AL, Oct 2 1961, Dot 16309, US, 1962; ‘Anna’, Nashville, Jul 1962, Dot 16387, 1962; ‘Go Home Girl’, Nashville, c.Sep 1962, Dot 16425, 1963; ‘(Baby) For You’ c/w ‘The Other Woman’, Nashville, 29 Oct 1965, Sound Stage 7 2556, US, 1965; ‘Burning Love’, Memphis, Aug 1971, on Arthur Alexander, Warner Bros. 2592, US, 1972; ‘Every Day I Have To Cry Some’, Muscle Shoals, Jul 1975, Buddah 492, US, 1975; A Shot of Rhythm and Soul, Ace CH66, London, 1982; Nashville, 12-17 Feb 1992, Lonely Just Like Me, Elektra Nonesuch 7559-61475-2, 1993. Special thanks for input & detail to Richard Younger, author of Get a Shot of Rhythm & Blues: The Arthur Alexander Story, Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2000; quote is p.168.]